Lumiere Press

By Kristen Adlhoch

Parenthesis, 2013

From its earliest incarnations as a paper-based medium, photography has been closely intertwined with book publishing. Just five years after William Henry Fox Talbot patented the first viable positive/negative photographic process in 1839, he published one of the earliest photography books. Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, a six-volume fascicle published between 1844 and 1846, proposed a variety of uses for the new medium in the service of science, art, archaeology and history, illustrating each example with one of Talbot’s own tipped-in calotypes. The text of The Pencil of Nature is pointedly didactic, and the subtext is a clear defence of the paper calotype against its rival, the French daguerreotype, a process that was unsuitable for reproductions of any kind, particularly book illustrations. Indeed, instead of labelling Talbot as the first person to employ photographs in the service of a book publication, we might more accurately describe him as the first person to employ a book publication in the service of photography.

Reflecting on the oeuvre of contemporary bookmaker and photographer Michael Torosian brings to mind Talbot’s incunabula. This is not due to any overt similarities between their publications, but because The Pencil of Nature implies a conviction that Torosian articulates: ‘the book is the medium of photography.’ This dictum has proved a successful formula for Torosian’s Lumiere Press – the only fine print book press devoted solely to photography – which in 2011 marked both the twenty-fifth anniversary of its publishing programme (beginning in 1986 with Edward Weston: Dedicated to Simplicity) and the release of its twenty-first title. Beneath the outward simplicity of Torosian’s statement lies a complex and multifaceted history of a hybrid medium – the photography book – that is more than the sum of its parts. In this context, Lumiere Press stands poised between two different photography book traditions: on the one hand, that of the hand-printed artists’ books of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; and, on the other hand, the widely produced photography books that began to proliferate prior to World War Two. The bridge that spans these two genres is modernism. In the terms of the history of photography, modernism signified the rejection of the painterly qualities and subject matter of pictorialist photography that had predominated in artistic photography in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Modernist photography practice and theory between the wars focused on the inherent qualities of the medium, such as the distortions created by the camera’s optics; the effect of different perspectives; and the detail and sharpness of the photographic negative/print. the compatibility of books and photographs logically begins with their mutual flatness and paper bases. Photographs, as Torosian points out, unlike media such as painting and sculpture, can be printed in such a way that the reproductions remain true to the aesthetic (and, at times, even the size) of the original print. It was by way of his own photography that Torosian came to bookmaking: frustrated by his lack of input into the design of a catalogue of his work, he began studying bookbinding at evening classes, and immersed himself in the community of small presses that existed in Toronto in the late 1970s.

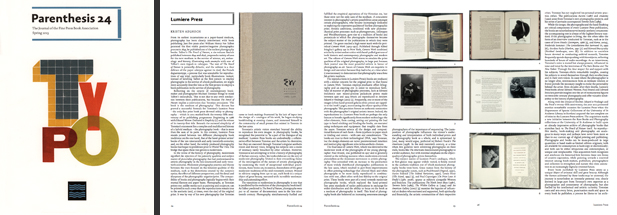

Torosian’s artistic vision stretched beyond the ability to reproduce his own images: in photography books, he recognised the potential to ‘be a part of the dialogue of my medium.' Lumiere Press books are undoubtedly a collaborative effort between Torosian and the artists he chronicles, but they are executed through Torosian’s singular aesthetic vision and literary voice, bringing his subjects into a realm of intimacy rarely broached by other scholars. However, Torosian is not attempting to write a history of photography of the last century; rather, his books elaborate on the story of modernist photography. United in their overarching theme of the investigation of the nature of artistic photography by examining the work of exceptional individual practitioners, these books are, in essence, descendents of the great modernist traditions of the mid-twentieth century. Printed in editions ranging from 150 to 250, each book is a unique object of great beauty, executed with incredible workmanship and painstaking effort.

The transition to modernism in photography is one that is paralleled by the evolution of the photography book itself. As Talbot predicted in The Pencil of Nature, photographs were put to all manner of documentary uses in the late nineteenth century. Photography simultaneously fuelled and fulfilled the empirical aspirations of the Victorian era, but these were not the only uses of the medium. A concurrent interest in photography’s artistic possibilities arose amongst certain photographers, who became increasingly dedicated to exploring the expressive qualities of the fine photographic print. Artistic ambitions, combined with new photomechanical print processes such as photogravures, collotypes and Woodburytypes, gave rise to a tradition of books and periodicals in which the photographs themselves became the subject matter of the publications in which they were printed. The genre reached a high water mark with the periodical Camera Work (1903–1917). Published through Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery 291 in New York, Camera Work combined articles by artists and art critics with hand-pulled gravures of both historic and contemporary photographs and modern art. The editors of Camera Work strove to emulate the print qualities of the original photographs, in large part because their journal was the most powerful vehicle in favour of photography-as-art. Issues of Camera Work are exquisite in design and execution because they had to be, at a time when it was necessary to demonstrate that photography was a bonafide artistic medium.

The reproductions in Lumiere Press’s books are produced with a similar concern for the original print to that found in Camera Work. Torosian employs stochastic offset lithography and an exacting eye in order to reproduce faithfully all manner of photographic processes, such as Edward Steichen’s rare mixed-process palladium prints made between 1916 and 1923 which are reproduced in Steichen: Eduard et Voulangis (2011). Frequently, one or more of the images (often hand-printed gelatin silver prints) are tipped-in to the book’s pages, accentuating the object-quality of the photographs. This precision fosters an authentic connection with the photographer’s original artistic intent. Indeed, the reproductions in a Lumiere Press book are perhaps the only feature to benefit significantly from modern technology: the ther elements, from casting, setting and printing the lead type to hand stitching and binding the books, are executed using techniques and equipment that roughly date from the 1920s. Torosian selects all the design and compositional features of each book – from typefaces to paper stock to binding and covers – with care and consideration. ‘The books are true to their technological DNA,’ says Torosian, but the design elements are never predetermined: intuition and instinct play significant roles in his aesthetic choices.

The final issue of Camera Work, which was devoted to the modernist work of the photographs of the young photographer Paul Strand, was published in 1917 and is generally viewed as the defining moment when modernism overtook pictorialism as the dominant movement in artistic photography. This coincided with an increase in the production of more widely distributed photographic publications in the late 1920s, which resulted in part from improvements in offset printing technology that allowed black and white photographs to be more easily reproduced in combination with text, albeit often with less fidelity to the originalprint. These books were part of a trend towards modernist photography books, which replaced the hand-printed fine press standards of earlier publications in exchange for wider distribution and the ability to focus on the book as a medium of photography in itself. This kind of photography book also bolstered an increasing awareness amongst photographers of the importance of sequencing. The juxtaposition of photographs influences the viewer’s understanding and interpretation of both individual prints and the photography book as a whole, and is epitomised by (and, many would argue, perfected in) Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958). In the mid-twentieth century, at a time when few galleries were exhibiting photographs on their walls, books like The Americans disseminated photography to a wider audience, but with minimal emphasis on the object quality of photographic prints themselves.

The subject matter of Lumiere Press’s catalogue, which at first glance may appear widely varied, is firmly rooted in the aesthetic tradition out of which modernist photography books were born. Great names from the history of the photography canon, such as Paul Strand (Orgeval, 1990), Aaron Siskind (The Siskind Variations, 1990), Lewis Hine (Ellis Island, 1995), and Paul Caponigro (On Prior Lane: A Firefly’s Light, 2008), appear as subjects alongside Weston and Steichen. The publications The Ninth Street Show (1987), Toronto Suite (1989), The Witkin Gallery 25 (1994) and An American Gallery (2007) examine the legacies of influential art dealers who nurtured and supported, both spiritually and financially, the artistic communities of their respective 26 Lumiere Press cities. Torosian has not neglected his personal artistic practice, either. The publications Aurora (1987) and Anatomy (1993) arose from Torosian’s own photographic projects, and his series of portraits accompanies Toronto Suite (1989).

While the design, the photographs and the hand finishing are critical components of every Lumiere Press publication, the books are nonetheless never merely aesthetic ornaments: the accompanying text is always of the highest literary standard. If the photographer is living, the text often takes the form of an interview conducted by Torosian, such as in the cases of Dave Heath (Extempore, 1988, and Korea, 2004), Frederick Sommer (The Constellations That Surround Us, 1992), Gordon Parks (Harlem, 1997) and Edward Burtynsky (Residual Landscapes, 2001). In addition to countless hours devoted to conducting archival research, Torosian frequently spends days speaking with his subjects, collecting hundreds of hours of audio recordings. As an interviewer, Torosian’s voice is muted but always present, influenced in tone and tenor by the interviews of The Paris Review and The New Yorker. Through his clear respect for and rapport with his subjects, Torosian elicits remarkable insights, coaxing his subjects to reveal themselves through their recollections and in their own voices. In cases where the photographer is no longer alive, reminiscences from an intimate relation or friend provide the necessary insight to evoke the personality behind the artist. Even decades after their deaths, Lumiere Press books about Edward Weston, Paul Strand and Edward Steichen provide insights into the art of monumental figures in twentieth century photography and offer valuable scholarship to the history of photography.

Along with the release of Steichen: Eduard et Voulangis and the Press’s twenty-fifth anniversary, the year 2011 presented another remarkable occasion for Lumiere Press when the Department of Special Collections of the University of St Andrews Library in Scotland acquired the last complete set of titles in the Lumiere Press archive. The acquisition marks a new initiative between the Rare Books and Photography Collections at the University of St Andrews to build upon an already impressive archive of photography books that stretches back to The Pencil of Nature itself. As reproducible media, bookmaking and photography are analogous in many ways, and perhaps have never been more so than in our current age of digital printing and publishing. Photographs and books can be mass-produced in large quantities or hand made as limited edition originals; both are available for consumption in hard copy or electronically; and both can be either ubiquitous and commonplace, or unique and irreplaceable. This acquisition both recognises and reinforces the historical link between these two forms of creative expression, while pointing towards a renewed interest among bookmakers, publishers, photographers and collectors to strengthen and sustain this close association in an increasingly digitally oriented future.

Every book published by Lumiere Press exists as a unique object of artisanal skill and great beauty. Although the themes addressed by these books may be universal, the journey is nonetheless an intensely personal one, clearly derived in large part from Torosian’s own expertise as a photographer and connoisseur of photography, but also fuelled by his intellectual and artistic curiosity. Torosian casts and sets every letter, punctuation mark and space in every book he publishes, a process he likens to ‘an architect setting every brick in a building he’s designed.' There is no doubt that Torosian has made great contributions to photography scholarship. But with his work through Lumiere Press, he also continues to influence and transform the very specialised medium of fine press photography books, of which he is an uncontested master.